Next: PRINCIPLES OF MEASUREMENT

Up: GEOMETRICAL CLOCKS

Previous: Fourier Compatibility

Contents

Time and space acquire their meaning from measurements,

i.e. identifications of a relationship by means of a unit that

serves as a standard of measurement. The measurement process we shall

focus on is based on the emission, reflection, and reception of radar

pulses generated by a standard geometrical clock.

Such a clock consists of a pair of Fourier compatible radar units,

say, A and B. Their reflective surfaces form the two ends of a

one-dimensional cavity with its evenly spaced spectrum of allowed

standing wave modes in between. The operation of the geometrical clock

hinges on having an electromagnetic pulse travel back and forth

between the reflective ends of the cavity. The back and forth travel

rate is determined by the separation between the cavity ends. This

rate need not, of course, be constant in relation to the atomic clocks

carried at either end. A geometrical clock with mutually receding ends

would exemplify such a circumstance.

The definition of a geometrical clock is therefore this: it is a

one-dimensional cavity

- whose bounding ends are Fourier compatible and

- which accommodates an electromagnetic pulse bouncing back and forth

between the left and right end of the cavity.

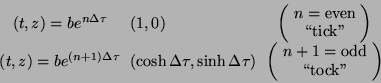

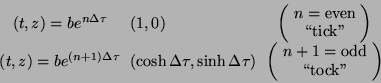

This bouncing action forms the tick-tock events of the clock. If the cavity

is expanding inertially, these events are located at

|

(2) |

along the two straight world lines of radar units A and B in spacetime

sector  . Here

. Here

is the Doppler frequency shift factor and  is the fixed

comoving separation between A and B. The constant

is the fixed

comoving separation between A and B. The constant  is the Minkowski time

when the geometrical clock strikes zero.

is the Minkowski time

when the geometrical clock strikes zero.

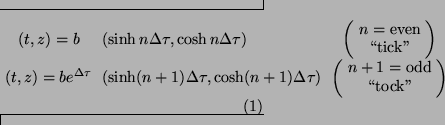

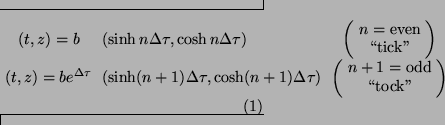

For a clock with ends subjected to accelerations  and

and

, the ticking events are located at

, the ticking events are located at

along the two hyperbolic world lines of A and B in boost-invariant sector  .

Here

.

Here

is the pseudo-gravitational frequency shift factor between them, and

is the boost time between a ``tick'' and a ``tock''.

is the boost time between a ``tick'' and a ``tock''.

The spacetime history of such clocks and their bouncing pulses are

exhibited in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2:

Spacetime history of

an inertially expanding clock and the null trajectories of trains of

emitted and received pulses (light lines) whose emission and

reception is controlled by the internal pulse (heavy line) bouncing

back and forth between A and B.

![\includegraphics[scale=.5]{inertial_clock_plus_nullrays}](img47.png) |

Figure 3:

Spacetime history

of an accelerated clock and the null trajectories of trains of

emitted and received pulses (light lines) whose emission and reception is controlled by the

internal pulse (heavy line) bouncing back and forth between A and B.

![\includegraphics[scale=.5]{accelerated_clock_plus_nullrays}](img48.png) |

To serve its purpose, a geometrical clock AB emits and receives pulses

of radiation. When the internal pulse strikes radar unit A its

transmitter and its receiver are turned on only for the duration of

the pulse. This causes A to emit a pulse and to register the reception

of a pulse from the outside, if there is one coming. When the internal

pulse has bounced back to B, an analogous emission and reception

process takes place at radar unit B. It follows that that the

tick-tock action of the internally bouncing clock pulse determines a

set of external pulses moving to the right and to the left. The

history of these pulses together with the clock that controls them is

depicted by Figures 2 and

3 for an inertially expanding and

accelerating clock respectively.

Next: PRINCIPLES OF MEASUREMENT

Up: GEOMETRICAL CLOCKS

Previous: Fourier Compatibility

Contents

Ulrich Gerlach

2003-02-25

![]() and

and

![]() , the ticking events are located at

, the ticking events are located at

![]() .

Here

.

Here

![\includegraphics[scale=.5]{inertial_clock_plus_nullrays}](img47.png)

![\includegraphics[scale=.5]{accelerated_clock_plus_nullrays}](img48.png)